We are driven to Crossfit for many reasons. Some need that feeling that they “aren’t alone,” in chasing their fitness-goals while others lacked intensity in their workouts.

You Don’t Just Want Glutes, You Need Glutes

Crossfit gets wide recognition for these two reasons but little is said about the functional benefits regarding its selection of exercises. When I say function, I imply a transferable quality to “real-life.”

Real-life to me means living pain-free and having the capacity to chase after my little girl.

The common denominator for Crossfit exercises is having great functioning glutes. While Crossfit utilizes many different exercises from powerlifting and Olympic weightlifting, if you look closely you will see a “squat,” hidden in them somewhere. Let’s take a look at why having great glutes are a necessity and how to make them better by cleaning up your squat.

Your Butt is Your Engine

Having a strong backside is important to all of our foundational movements. This means your ability to run faster, jump higher, and squat heavier are all dependent upon your ability to generate force from your gluteus maximus. If your glutes aren’t strong enough then you will lack efficiency to do thing’s like climb mountains, balance on one leg, or quickly stop and change directions if you are being chased by a lion or heading after your 2 year-old.

To understand why this is, you need to understand just how muscle work. Think of muscle as a rubber-band. As you stretch that rubber band you can feel the tension build up in it (potential energy). If you let it go when the tension is fully built up, it will fling from your fingertips across the room. This is based upon the “recoil” principal in physics. Our gluteus maximus is part of continuous chain of muscles and connective tissue that displays this “recoil” effect often during Crossfit WODs. Each time that we take a step during a run or hinge at the hips, we stretch out our glutes and rely on this “stretch-relex,” to move us. This makes our glute muscles part of a powerful engine called the posterior chain.

Prevent Knee Pain

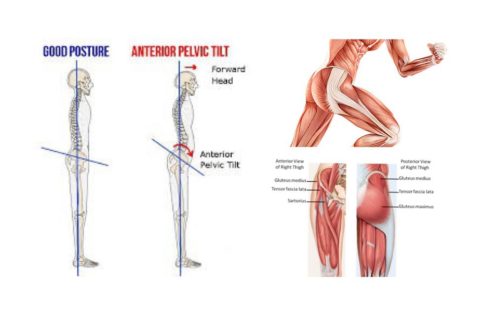

Your posterior line has a huge responsibility to swing your hips forward but also have the responsibility to keep your knees in proper alignment when we do activities such as running, jumping, and squatting. To understand this, let’s look at anatomy of gluteus maximus real quick.

Our glutes originate on the back of our hip and wrap around to the side of our leg at our IT band. Our IT band effectively runs from the side of our leg, into our lower leg and under our foot. As our ankle, knee and hip bend, when we do things like running or jumping, our glutes act as an anchor for our IT band to hold on to navigate the alignment of the knee with the ankle and the knee with hip.

If the glutes are weak, then the knee becomes more of a slave to the foot and ankle. Usually this means, it tracks poorly (that is the clicking your hear). Track poorly for long enough or with too much stress and you open the door for injury and pain.

Saves your Back

There are many reasons why so many people feel back pain, but one of the most common is a pelvis that isn’t lined up correctly. If you can lie flat on your floor and there is a big arch in your lower back then it is very likely you have an excessive anterior pelvic tilt. People that have an excessive anterior tilt likely have tight hip flexor muscles that are preventing there hip from functioning the way that is supposed to.

Generally, what happens is that the pelvis gets stuck in a position in which the lower back musculature is forced to tighten up. Your body ends up looking for alternative ways to move. When there is too much compensation too much of the time, we end up having a multitude of problems. The structural malalignments in your hip and pelvis can create all sorts of irritation from spasms in the lower back to radiating pains in the lower leg and foot.

As Crossfitters so many of the exercises we are asked to do, involve flexing at the hip and cause a shortening of the hip flexors and promote this anterior tilt. Strong glutes create a fully functioning hip and can prevent these pains.

That being said, learning to squat effectively is vital to our ability to not only function at a high-level, but feel less pain. Every time we sit on the toilet we get a chance to practice this primal pattern but with all these repetitions also come faults.

Here are the five most common back squat faults for coaches and athletes to look for:

1. Not Hitting Depth

According the Crossfit standards, proper squat depth is getting the hip crease below the knee. When compared to partial squats, hitting squat’s for depth encourages an increase in overall lower-body musculature, increases in sprint speed and vertical jump, is healthier for the spine and knees, while at the same time increases caloric expenditure to achieve an overall more athletic body. All this being said, full-squat depth requires a greater amount of flexibility and mobility than partial repetition squats. There are two important flexibility issues to consider when assessing an athletes ability to hit squat depth.

Hitting squat’s for depth encourages an increase in overall lower-body musculature, increases in sprint speed and vertical jump, is healthier for the spine and knees, while at the same time increases caloric expenditure to achieve an overall more athletic body.

hip crease

1. Ankles: From the top-down, squatting is defined as a vertical displacement achieved by bending at the hips, knees and ankles. An athlete can bend great from both the hips and the knee’s but if the ankles aren’t mobile, the other two joints will have their mobility comprimised. It is all too common to find athletes who lack dorsi-flexion and have a reduced capacity to bend at the ankle.

2. Glutes: To maximize our muscles full capacity to generate force, we first want to load it up. Remember the rubberband example from above. By dropping lower into a squat we are loading up our glutes which will allow us the recoil effect to fire us back up. By missing any extensibility from the posterior chain we are limiting not only our ability to get to depth but our ability to generate force as well.

2. Knees Cave Inknee cave 2

Proper squat technique involves keeping your knees out and in-line with your first two toes. When the knees fall out of this alignment, they take on more stress than they like. Remember from above that the gluteus is part of the that lateral line. The gluteus maximus originates at the lumbosacral fascia, the sacrotuberous ligament, and the illium of the pelvis. This muscle then insert into the side of the leg at the illiotibial band.

What this means, is that in addition to extension of the hips, the glute max is a powerful external rotator of the femur. Keeping the knees out and femur externally rotated loads up the glute maximus to allow for a powerful force production as the hips extend. Losing this position during the squat reduces our force generating capacity and increases the chance for injury. We need glutes that are active and here are two things that can help this:

Cues – Have your coach watch as you squat. Many errors are fixed when someone else see’s them and cues you as you move. This is why it is common place to hear “Knee’s out!!!” yelled in boxes around the globe.

Glute activation- Sitting too much during the day can put our glutes to sleep. In addition to mobility drills, it is very important that prior to squatting we “wake up,” our glutes. There are many activation exercises that we can do to help this such as monster bands walks and side-lying clams.

3. Falling Forward

Athletes will often have the appearance of “falling forward” when coaches see their knees travel too far in front of their toes. Of course we can try to address this with soft tissue work on the calves and rectus femoris, but there might be a technique fault we need to address first. When assessing an athletes squat technique and form there really is one biomechanical factor we need to pay attention to during an athletes set up which can contribute to this fault.

Bar placement – The key with understanding bar placement on the back really ends having more to do with the feet than anything else. Ultimately we are trying to place the bar in a position on our back to allow our weight to be centered over the talus bone in our foot. The talus bone is the weight-bearing bone in our foot and should be lined up directly underneath the knee. If we can keep the path that the bar travel directly over the talus then we will be able to maximize force production from our strong gluteal muscles as long as their extensibility isn’t compromised.

Athletes who “fall forward,” end up rocking their weight from the heel of their foot to the ball of their foot. This puts the calf muscles in a position in which they need to work overtime to prevent the rest of the body from toppling over. Again, I offer three ways to fix this:

1. Cues: A good coach is a “yeller” and if you are falling forward you will hear “Weight on your heels!”

2. Lower the bar on your back: From an anatomical perspective, the lower you can keep the bar on your back the easier it will be to keep the bar in a neutral position over your mid-foot and reduce the amount of movement needed from the ankle.

3. Increase dorsiflexion: The hip and the knee are at the mercy of the ankle. If the ankle can’t bend, then everything gets messed up above.

4. Lead with Chest

Leading with the chest refers to over-arching at the lower back when coming up from the deepest part of a squat. Remembering our definition of a squat as a vertical displacement, is crucial to understanding just why someone would “lead with their chest.” Our brain is pattern oriented. If the goal is to ascend from the bottom position, then it will always find a way to “go up,” even if that means compromising ideal movement. Here are two things to consider when addressing an athlete who is leading with the chest up:

1. Cues: Once again, sometimes the easiest way to fix a movement problem is simply to say something. A lot of times an athlete won’t understand a verbal cue and will need something tactile. This is why a weight-belt is commonly used. By keeping abdominal pressure against the weight-belt, the athlete is able to keep their core rigid and their spine protected, thus preventing an arch from the lower back.

2. Widen the stance: As previously mentioned our glutes are strong and should be thought of as an engine. If we see a lead with the chest, our brain is finding a way to make up for a weakness in our glutes. Widening the stance will increase the distance of the origin from the insertion points of the gluteus maximus. Once again, this allows the muscle to stretch out on the descend into the bottom of your squat and increase the recoil effect.

5. Descent Speed

This a big problem and really displays an interaction of psychology and the expression of human movement. To understand what I mean, takes an understanding of two types of muscle contractions.

1. Concentric: A concentric contraction is the shortening of a muscle. Think bicep curl. Think lifting a weight from the ground. We generally measure the amount of force produced as a result from a concentric contraction. During the squat this occurs when we change directions ascend from our most bottom position.

2. Eccentric: An eccentric contraction occurs when a muscle lengthens out. Think lowering the weight during a bicep curl. Think returning the weight to the ground. This is what is happening when we descend into the bottom of a squat. Basically, an eccentric contraction’s are our braking system and slow us down.

Typically as the weight increases a sense of fear and lack of confidence begins to pop up in our brain. With this we become more cautious. From a muscular contraction standpoint, this means we “leave our brakes on.” Instead of fully “dropping into a squat,” and building up the required potential energy, we end up wasting energy by slowing ourselves down. This is part of the engineering of a healthy nuero-muscular system. Think about it. Without this innate response, we would end lacking the control required to balance heavy loads. For the ultimate goal of developing strong glutes this is more often a problem than productive, as athletes end up missing the proper depth needed to express full range of motion. To fix this, here are two things to consider:

1. Your pelvic alignment is off: A common postural deviation is a posterior pelvic tilt. Those with this deviation have a glutes that are tucking their pelvis under and have reduced capacity to lengthen, thus the “brakes,” are always on. Your muscles will only do what your bones tell them to do.

2. Your quads might be blasted: If your behind is not working, another part has to pick up the slack. This could lead to many deviations but usually means the quads suffer the burden of slowing our body down as we drop into a descended position during a back squat.

Post your comment